From the Dalkon Shield IUD to thalidomide to three-wheel ATVs, product liability lawsuits have helped identify dangerous and defective products in the marketplace. Juries have then often sent a message to manufacturers that the community will not tolerate products that kill and maim. Even then, manufacturers do not always act responsibly and promptly to recall their defective or dangerous products. And the last thing they want to do is issue a recall of their product during active litigation.

Pursuing safety through litigation, however, The Cooper Firm’s efforts have resulted in no less than three mid-case recalls. And a single letter the Firm wrote to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (“NHTSA”) led to NHTSA fining a carmaker $35 million for its untimely reporting of a massive safety defect. The three lawsuits and the extensive discovery conducted in them resulted in these mid-case recalls. And thus, improved safety and saved lives.

The Melton Mid-Case Recall

The Cooper Firm’s first mid-case recall goes back to 2010, when Beth and Ken Melton first came to our firm. They wanted to know why their daughter, 29-year-old Brooke Melton, died on May 10, 2010, in an inexplicable wreck while

The Cooper Firm’s first mid-case recall goes back to 2010, when Beth and Ken Melton first came to our firm. They wanted to know why their daughter, 29-year-old Brooke Melton, died on May 10, 2010, in an inexplicable wreck while

driving her Chevrolet Cobalt car. The car had lost all power to its ABS system, its lights, its airbag, and its power steering—resulting in her crash. A defense lawyer from another case referred the Melton parents to The Cooper Firm.

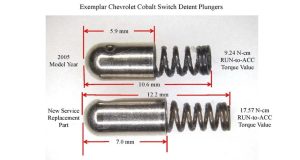

As we investigated, we learned that GM knew about airbag non-deployments but had not connected it to the ignition. As one investigator later said, GM did not know how its own cars worked. Wreck turbulence or even heavy keys on the GM ignition switch caused it to move from RUN to ACC, shutting off the power. As we conducted discovery, we did something GM had not yet thought to do: we took apart a Cobalt ignition switch. Our expert found that the detent spring in it and later cars (which were not failing) were quite different in spring length and torque. While we focused on the switch, GM had been focusing on the airbag and the “root cause of their non-deployments, all the while calling the accessory switch problem, which caused stalls, a “customer convenience issue.” And this was one GM knew about before it began selling the Cobalt cars.

In 2014, the middle of the Melton case, GM instituted its first of many recalls to find and fix the defective ignition switches in its many cars. This defect may well have been GM’s biggest scandal. It led to over 30 million cars being recalled. GM employees were fired. There was talk of a criminal investigation.

In 2014, the middle of the Melton case, GM instituted its first of many recalls to find and fix the defective ignition switches in its many cars. This defect may well have been GM’s biggest scandal. It led to over 30 million cars being recalled. GM employees were fired. There was talk of a criminal investigation.

You can google “Brooke Melton GM ignition switch” and read scores and scores of articles about it. Most are quick reads. If you have more time, read the Valukas Report, which GM commissioned ostensibly to get to the bottom of the switch failures. Our opinion was that the mea culpa Valukas Report was done more to undercut punitive damages claims against GM than to come clean about the cover-up of the switch defects. The Report, sad but fascinating throughout, details GM’s tragicomic engineering and business errors that led to 124 deaths, 274 injuries, 60 recalls, and cost GM over $3.8 billion dollars.

The $35 Million Letter

But sometimes there is still more to be done. As we dug into the Melton case discovery, it became clear to us that GM had not timely notified NHTSA about the ignition switch defects. On February 19, 2014, we sent a formal Timeliness Query to NHTSA, asking it to investigate both the timeliness and scope of GM’s Cobalt recall. Our four-page letter detailed what GM knew (as disclosed in discovery) and when they knew it.

On February 26, 2014, NHTSA opened its formal Timeliness Query (TQ 14-001). The TQ was “opened to evaluate the timing of GM’s defect decision-making and reporting of the safety defect to NHTSA.” In the following weeks, while it stalled giving NHTSA information, GM expanded its recall to include millions more GM vehicles. On May 16, 2014, NHTSA and GM entered into a Consent Order as part of the TQ and Recall No. 14V-047.

In the Consent Order, GM admitted that “it violated the Safety Act by failing to provide notice to NHTSA of the safety-related defect within . . . five working days” as required under federal law. In truth, of course, GM dawdled for years before notifying NHTSA. In any event, GM agreed to pay “the maximum civil penalty for a related series of violations in the sum” of $35 million dollars. It is refreshing to learn that the pen is sometimes still as mighty as the sword.

The Gaddy Mid-Case Recall

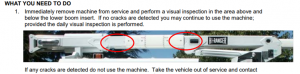

We met Jeff Gaddy in 2014. A tree cutter in his family’s business, Jeff became a paraplegic when the boom on his Terex XT series aerial lift broke and dropped him almost four stories. As Jeff’s lawsuit progressed, it became clear that the lower portion of the Terex boom was made from steel that was not strong enough for that specific area of the lift boom. Discovery showed that Terex’s steel supplier sent Terex a weaker steel to make some of its booms. We also discovered more than 180 other cracked Terex booms.

On June 9, 2016, again mid-case, Terex recalled 1,300 of its XT series aerial lifts.

Terex told boom owners that the “lower boom may have material which does not conform to specification. If the lower boom fails there is risk of injury due to the boom and attached basket falling from height.” Terex agreed to inspect and replace the nonconforming booms.

The Terex boom recall came far too late for Jeff, but he knows his decision to investigate and sue Terex saved other workers from suffering a similar fate. In 2019, his case settled for a confidential amount during trial in federal court in Atlanta.

The Hall Mid-Case Recall

We met the family of Orlando Hall in 2017. They came to us because their father had been crushed to death while working with a Schwarze M6 Avalanche street sweeper. On September 17, 2017, while trying to respond to a fault light on his console, Orlando climbed onto an open area of the sweeper to look around. His leg hit an exposed toggle switch, which immediately shot a heavy conveyor forward. It caught him in his chest against the debris hopper and crushed him.

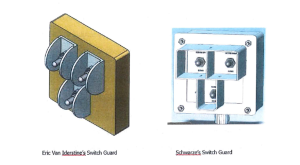

We filed suit in 2018 and conducted thorough discovery about the sweeper design and toggle switches. We learned that Schwarze had moved the toggles from a safer spot on the sweeper to the more exposed location on an outside switch box. And did so with no safety analysis whatsoever. We contended that Schwarze should have covered the toggles with a guard, adhering to the long-held engineering hierarchy of “design out the hazard or guard the hazard or warn about the hazard.” Our expert, Eric Van Iderstine, P.E., designed working switch guards, and he told Schwarze in March 2020 that guards were needed to guard the toggles. Yet, Schwarze did nothing. On August 10, 2020, another man, Jason Ostwald, in Mesa, Arizona died in the same way on the same sweeper with the same exposed toggles.

Relentlessly Pursuing Justice

We do not expect a recall home run in the middle of every product liability case we take. We will, however, pursue each one of them as if we will cause a recall if one is needed. Candidly, such mid-case recalls do not happen very often. In fact, they are uncommonly rare, but they remain our common goal from case to case to case.